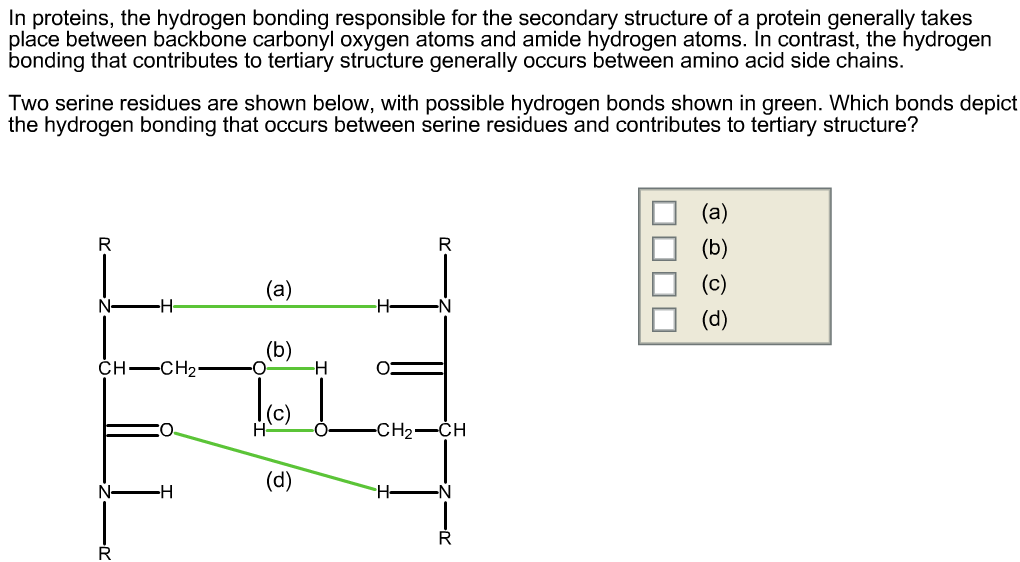

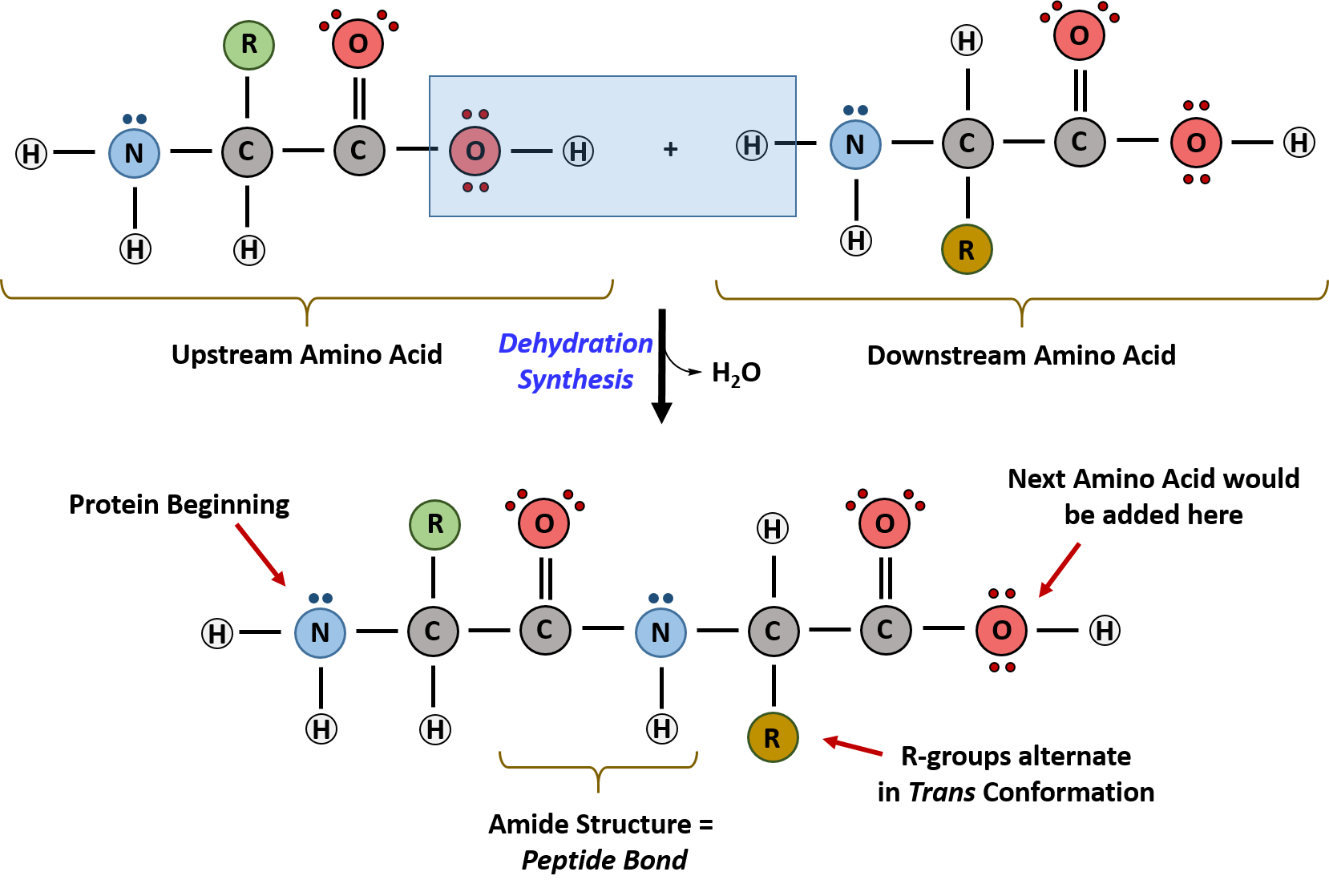

We then generated corresponding sets of repeating-peptide backbones by randomly sampling di-peptide and tri-peptide conformations (avoiding intra-peptide steric clashes), and then repeating these 4–6 times to generate 8–18-residue peptides. We generated large sets of repeating-protein backbones that sampled a wide range of superhelical geometries (see Methods). All repeating polymeric structures trace out superhelices that can be described by three parameters: the translation (rise) along the helical axis per repeat unit the rotation (twist) around this axis and the distance (radius) of the repeat unit centroid from the axis 18, 19 (Fig. To address the first challenge, we reasoned that a necessary (but not sufficient) criterion for in-phase geometric matching between repeating units on the designed protein and repeating units on the peptide was a correspondence between the superhelices that the two trace out. The second challenge is important for achieving a high binding affinity: in conformations other than the α- and 3 10-helix, the NH and C=O groups make hydrogen bonds with water in the unbound state that need to be replaced with hydrogen bonds to the protein upon binding to avoid incurring a substantial free-energy penalty 15. The first challenge is crucial for modular and extensible sequence recognition: if individual repeat units in the protein are to bind individual repeat units on the peptide in the same orientation, the geometric phasing of the repeat units on protein and peptide must be compatible. This requires solving two main challenges: first, building protein structures with a repeat spacing and orientation matching that of the target peptide conformation and, second, ensuring the replacement of peptide–water hydrogen bonds in the unbound state with peptide–protein hydrogen bonds in the bound state.

We set out to generalize peptide recognition by modular repeat-protein scaffolds to arbitrary repeating-peptide backbone geometries. By redesigning the binding interfaces of individual repeat units, specificity can be achieved for non-repeating peptide sequences and for disordered regions of native proteins. Crystal structures reveal repeating interactions between protein and peptide interactions as designed, including ladders of hydrogen bonds from protein side chains to peptide backbones. The proteins are hyperstable and bind to four to six tandem repeats of their tripeptide targets with nanomolar to picomolar affinities in vitro and in living cells. We design repeat proteins to bind to six different tripeptide-repeat sequences in polyproline II conformations. The remainder of the protein sequence is then optimized for folding and peptide binding. We use geometric hashing to identify protein backbones and peptide-docking arrangements that are compatible with bidentate hydrogen bonds between the side chains of the protein and the peptide backbone 12. Here, inspired by natural and re-engineered protein–peptide systems 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, we set out to design proteins made out of repeating units that bind peptides with repeating sequences, with a one-to-one correspondence between the repeat units of the protein and those of the peptide.

However, designing peptide-binding proteins is challenging, as most peptides do not have defined structures in isolation, and hydrogen bonds must be made to the buried polar groups in the peptide backbone 1, 2, 3. General approaches for designing sequence-specific peptide-binding proteins would have wide utility in proteomics and synthetic biology. Nature volume 616, pages 581–589 ( 2023) Cite this article

De novo design of modular peptide-binding proteins by superhelical matching

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)